- Home

- Jan Bozarth

Lilu's Book Page 2

Lilu's Book Read online

Page 2

“I’m not troubled,” I said, responding to our word’s secret meaning. “You worry too much.” I spun around, hoping to avoid her gaze. I removed three beige linen napkins from the sideboard, rolled them, and slipped each inside a hand-carved ring. Then I placed one napkin beside each dinner plate.

Tandy hadn’t moved.

Oh, man, she drove me nuts when she did that.

“Tan, cut it out!” I said.

Aurantiado.

“Nothing’s bothering me,” I said.

“Aurantiado!” said Tandy. This time no twin telepathy needed.

I sighed, then picked up the basket.

Tandy looked at me, not understanding.

I said, “Remember when Mom made this basket? It was the first time she tried teaching us the family tradition of weaving.”

Tandy shrugged. “Of course I remember,” she said. “That’s when we started our business with the baskets, bracelets, and seashell necklaces.”

“Do you remember how easy it was for you to follow along and how hard it was for me?”

Tandy put her hands on her hips and shook her head. “No, I don’t remember that.”

“C’mon, Tandy. We couldn’t have been more than seven at the time. This stuff.” I swept my hand around, turning slowly, indicating all the family treasures made by my mother and our ancestors—tightly woven baskets, loosely bound place mats with beads or other adornments added to the dried grasses and reeds, lap blankets crocheted with organic yarns for cool winter nights on the beach. My mother was like her mother and her mother before her, a whiz at working with her hands.

Tandy caught on easily. Me, not so much.

“Lilu, you’re great with the bracelets. And animals. And seashells. Think of all the money you’ve raised to donate to save the sea turtles, the whooping cranes, everything. We’re selling tons of crafts—stuff we both made—thanks to the website George set up.”

George was some sort of business guru. Tandy was right; thanks to him, we’d sold a lot more bracelets and crafts online than we’d ever sold at the craft fairs. We made a great team, my sister and I. She didn’t get it, though. I wasn’t going this nutso over baskets or bracelets or websites.

It was us. Her and me. It was like we were being pulled apart by some enormous tide. Like when we finally made it to shore, we’d be in two separate places, and I’d be all alone.

My sister huffed and rolled her eyes. “Hello! Baby sister, are you in there?”

It was my turn for an eye roll.

“Who cares if you can’t weave a basket as well as someone else?” said Tandy. “Are you really going to be a basket weaver when you grow up? I don’t know how many Olympic divers also need to know how to make baskets, so I think you’re good.” Tandy took the basket from my hands and tugged me into a hug.

I clung to her for a second, then pulled away. My face felt warm. I was being a dope again. “So, tell me all about this musical you’re going to be in.…”

“We’ll always be ‘us,’ Little LeeLee.”

She caught me off guard. Maybe being born sixteen minutes earlier really did make a big difference. LeeLee. She hadn’t called me that since we were little.

Tandy grinned. “Stop being so mopey and dramatic, you little dope. I’m your big sister. I’m here for you.”

She pushed me toward the kitchen. “Now stop acting so serious, and go help Mom in the kitchen.”

I turned and snapped off a military salute to her. “Yes, ma’am!” I said.

When I pushed through the kitchen door, Mom was standing at the counter, pulling back the aluminum foil from the roasted chicken. The room filled with the scent of lemon pepper, fresh basil and oregano from our garden, and the delicious warm and sweet scent of citrus. It was Mom’s famous citrus roast. Beautiful circles of sliced orange and lemon covered the chicken’s crisp golden skin.

“Mom, that smells delicious!”

She gave me a sideways glance, then smiled. “You always did love this to death.” Then she turned away from the chicken and stared carefully at my face. It was like she was trying to memorize it—or look for something.

“Why are you looking at me like that?” I asked.

She gave a little laugh. “Sorry, kiddo. It’s just …”

For several loooooong seconds she was silent, and it freaked me out. Why was she looking at me like she had never seen me before? She took a deep breath, then let it out slowly.

“Lilu, I know you know, but I can’t help saying it anyway: I love you girls very, very much. You two are the meaning to my whole world.”

Uh-oh! We were definitely headed toward an Awkward Emotional Moment. When we were about eight, whenever Mom got this look on her face, we’d yell, “Oh no! Mom is trying to bond!” Then we’d run shrieking through the house.

She hugged me tight.

“Mom, let go. You’re going to break me!” I wanted to lighten the moment. Could she sense how confused and conflicted I’d been feeling about all the changes in our lives?

“Lilu, I know you’ve been pretty conflicted about all the changes going on,” she said.

I swear, it’s like she and Tandy have some sort of probe in my brain that tells them exactly what I’m thinking.

“Mom, I’m fine.”

“After dinner, when your sister goes to babysit, you and I are going to sit on the back porch and have some time for ourselves.”

I felt my eyebrows crinkle into question marks. In the stainless steel fridge, I saw my reflection distort, like in a fun-house mirror. My mother laughed. Then she pulled me into another hug.

“Mom! I’m at that age when too many hugs is just plain embarrassing. Can you please just tell me what’s up? Tan and I have talked to you about unauthorized bonding.”

“You guys …” Tandy pushed through the kitchen door and saw Mom still hugging me and me trying to break free. “Uh-oh!” she shrieked. “Unauthorized bonding!”

We all started running around like crazy people, through the kitchen and into the dining room. Mom was making kissy sounds and yelling, “I need someone to hug!”

Finally, Tandy was laughing so hard she dropped to the floor and said, “Stop! I’m starving. Less bonding, more eating.”

“Be right there,” Mom said. Then she added, “Tandy, go outside and get us a few fresh hydrangeas from the bush by the front door.” She whispered to me, “Shhh! Just girl talk. For us!”

“Hmm … if you say so,” I replied with an exaggerated eye roll.

She pinched my cheek, and I knew what was coming next—as soon as Tan left to babysit our cousin, also known as Problem Child, Mom was going to sit me down and engage in the itchiest of feel-good experiences: bonding.

I’d need to keep an eye on her. Especially if she wanted me to talk about my feelings from earlier.

How embarrassing would that be? Telling Mom I was having movie-of-the-week fantasies about our family getting back together. That kind of thing could get a girl into trouble.

2

Secrets of the Shell

Despite the warning lights and alarms going off inside my brain, I managed to enjoy dinner. It was delicious. The three of us talked about a bit of everything.

Mom was talking a mile a minute. She got like that when she was nervous or amped up. “I can’t wait to see you girls all dressed up as bridesmaids,” she said.

So this might sound a bit crazy, but as much as I fantasized about Mom and Dad getting back together, I was really looking forward to my mom’s wedding and wearing that totally beautiful blue dress with the tiny white and pink flowers at the waist.

Would it totally stink if Mom and George got married just for the ceremony, then we came back here to live with Dad again? (I’m guessing George would have some real issues with that plan!)

“I’ve set aside some pretty seashells that we can use like beads to decorate our headbands,” I said.

When Mom smiled at me, it was like seeing the sun rise. I couldn’t remember seeing he

r more beautiful—or happy.

Was she really that happy to be moving away from her old life?

My aunt Mary rang the doorbell while we were clearing the table. Tandy grabbed her iPod and raced for the door. She paused and asked, “LeeLee, sure you don’t want to come with?” She flicked her eyebrows up and down.

I glanced over and saw Mom’s face tighten. She really didn’t want me to go. Why?

“Nah, I’d better stay here,” I said. “You know Problem Child is no fan of mine.”

“Uh, Lilu, maybe if you stopped calling him Problem Child it’d help.”

I shook my head. “Um, no, I don’t think it would.”

“Well, see you in a few hours. Later!” And she was gone.

Mom and I finished putting the dirty dishes in the dishwasher and wiping down the counters. Then Mom suggested we get some dessert and something cool to drink and go sit on the back porch.

The alarms started blaring again.

“Mom, I’m still tired from this afternoon. Maybe I should—”

“Nonsense!” She cut me off. “Now help me with our after-dinner treat.”

A few minutes later, we headed for the back porch. Holding two large glasses filled with iced tea steeped with fresh peach and sprigs of fresh mint, I sat on the metal swing next to Mom. The back porch was screened and faced the ocean. The sky was dark, but the clouds from earlier had cleared. A full moon was hanging low over the ocean.

Mom handed me a plate with a slice of sweet potato pie, and I gave her a glass of tea and then took a big sip from mine. The tea smelled fresh, strong, sweet … but it couldn’t compare with the overwhelming scent of the ocean.

The back porch was my favorite part of the house. At the other end was a futon with an oversized cushion covered in fat blue and white stripes. I’d slept out here a number of times, and I always woke up feeling refreshed.

Three sides of the porch were screened, and the one wall was lined with antique shelves. Each shelf held baskets and jars filled with seashells. Our seashell collection was also strung together and hung around the room.

“You were terrific today at the pool,” said Mom.

I shrugged. Sitting so close to her, feeling the warmth of her skin, I felt cozy and safe. “The best part, I think, was seeing you in the stands next to Dad.”

Oh no! That just slipped out! I’m such a dope. This is exactly the type of thing moms are looking for when they set us up for special bonding time.

She turned toward me, and the swing creaked. “You miss him a lot, don’t you?”

I dropped my head back and let out a long sigh. “Mom,” I groaned. “I know you guys aren’t getting back together. And I know it’s not my fault or our fault like some kids think. And I know you’re very happy, okay?”

“Well, sounds like you’ve got it all figured out. Eat your pie, sweetheart,” Mom said.

I took a large forkful of the creamy sweet potato pie. “Mom, this is delicious. You know I could eat sweet potato pie every day!”

Mom set her plate on her lap and turned toward me. Her eyes studied me for a second, and then she said, “How about you and Tandy? Everything okay?”

Moms have that way about them, you know. They’re more than smart—they’re clever. Here she was letting me talk about her and Dad and everything, then out of nowhere she hits me with what’s really bugging me. I guess thinking I could hide it from her was silly. Mom always figures things out.

Still, if I had any chance of avoiding more mother-daughter bonding, I had to rely on the one trick in every kid’s book: denial. “Mom, me and Tan are fine. I’m fine. Really.”

“So you’re telling me you’re excited about moving and delighted with all the changes and ecstatic that your sister is developing other interests and is not spending as much time with you?” she asked.

I studied the pie on my plate and pushed a piece of crust back and forth. “I …” My voice broke. I tried to say something lighthearted, but it just got caught in my throat.

She reached over and squeezed my knee. “Lilu, baby, having you girls has been a constant blessing, a gift. I’ve watched you two blossom, watched your friendship, your special connection. I’ve watched it and loved it. But I know the two of you are at an age when you might not be quite as identical as you once were. Tandy is getting really involved in her singing and acting. She’s great at it. But I see the way you get whenever that stuff comes up. I guess what I want to say to you is don’t be afraid to let her go. Once you let her go, you give yourself permission to be all that Lilu was meant to be. You are a rare and beautiful person, Lilu Hart. Don’t be afraid of your uniqueness.”

Nothing to do with a speech like that but eat a few forkfuls of pie and let it sink in. Mom hummed while she ate. The tall, lush sweetgrass and foxtail alongside the house swished and swayed in the wind, lending a backup chorus.

“This is for you.” Mom held out her hand, and the moonlight flitted over the object in her outstretched palm.

It was a shell unlike any I’d ever seen. I reached out and took it from her. “It looks like a crescent moon,” I said.

Mom nodded, her half smile now almost hidden behind her forkful of pie.

“Hey, Mom, have you packed all the old seashell books? I’d love to look this one up. It’s amazing!”

She set her plate on the floor, lifted her iced tea, and took a long swallow. Then she said, “It is amazing, Lilu. But you won’t find it in any book. It is one of a kind, made by the sea and the moon specifically for our people, our ancestors, and passed down from generation to generation.”

“Like the baskets?” I squeezed my hand shut, pressing the cool, unusual shell into my skin. Then my hand opened wide as my mind whirred with the fear of damaging something so precious.

“Sort of like the baskets. But the crescent moon came before the baskets. Without the pure magic of this moon’s light, our family might never have found its way, would never have understood its purpose.”

I frowned. “You’re talking about Aventurine again, aren’t you?”

“Let’s take a walk,” she said.

The screen door snapped shut like a turtle’s mouth. As we moved toward the ocean, I glanced over my shoulder. Our house was candy pink with big, rolled tiles on the roof. Black shutters sat beside the windows. On nights like tonight, after a huge afternoon storm, we opened the windows to allow the ocean air inside.

An occasional strong gust of wind blew from the ocean, making me glad that I had used a red scarf as a headband to keep my unruly hair out of my face.

Mom led me to a jagged rock formation and began to climb. We were careful to place our feet in the crags and craters, moving carefully until we reached a lip of the rock face that flattened. With my eyes closed, I filled my lungs with the beautiful ocean scent, fresh and briny and alive. Whenever I was this close to the ocean, especially at night, it became a symphony in my head.

Mom interrupted my thoughts. “Lilu, you know your aunt Mary and I have talked a lot about Aventurine with you girls over the years.”

I nodded.

“Well, now it’s your time,” she said. “I didn’t know which of you girls would be first, but now I know it’s you.”

“Mom, you’ve always talked about Aventurine; you talk about it being such a cool, magical place. A place for strong women to figure out who they are and train to become fairy godmothers.…”

“That’s right.”

“So … it’s real? I thought it was just some sort of bedtime story.”

Mom’s laughter was deep and sweet. “No, baby, that was no bedtime story. Aventurine is definitely real.”

My knees buckled. My hand shut tight, and the shell dug painfully into my palm.

“Whoa!” Mom reached out and grabbed me. She helped me sit on the flat part of the craggy rock and didn’t take her arms from around me until I was sitting, facing the ocean, feeling the dampness of the surf against my skin.

“Umm, maybe next time you share life

-changing news with me, we can do it someplace more stable? Remember, I’m the one who isn’t that good with change!”

“Don’t worry, Lilu. You’ll be fine.” Mom squeezed my shoulder, and I let myself lean into her.

Then she lightly tapped the fist I was squeezing the shell in. “Relax,” she said. “You won’t lose it. When you need it, it will find you. Aventurine will teach you how to use it.”

I frowned again. This was crazy!

Mom smiled. “I’m going to ask for a favor.”

“What is it?”

When she looked at me, she took my hands in hers and said, “I want you to stop thinking so hard about how everything should be and what pieces should go where.”

Now it was my turn to smile. She had me. I sighed. “Okay, Mom. So, tell me again about Aventurine. Remind me how this is supposed to work.”

“Early on, I knew I was blessed with the gift of weaving stories,” she said.

“I thought our family’s skill is weaving baskets,” I said.

“Those are skills passed down from generation to generation. Skills that, if you believe in yourself and have faith, you, too, can develop. Or maybe you’ll develop other skills that work just as well. But my true ‘gift,’ that thing I knew I was meant to do more than anything else, that was writing screenplays for movies and television. It was what I’d dreamed of since I was a little girl. Writing allows me to speak with people in their language. Not the language of their ears, but the language of their hearts.

“Our family comes from the Songa Lineage. Crafting a story isn’t so different from crafting a basket. Instead of sturdy reeds, I take words out of the air and shape them into thoughts and emotions.”

I nodded. I hadn’t thought of it that way.

“So,” I said, “what is the Songo Lineage thing about?”

“The Songa Lineage. When famine threatened our ancestors’ survival in Africa, our queen spoke to the moon.”

“And the moon spoke back?” I asked.

Mom smiled again, her teeth as white as the shell. “More like the moon goddess. It turns out the moon needed us, too. It had gone off track and pulled the tides out of alignment. Our great ancestor, a woman known as Mama Akuko, herself a fairy godmother, saved the moon and the tides.”

Zally's Book

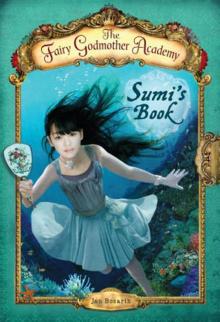

Zally's Book Sumi's Book

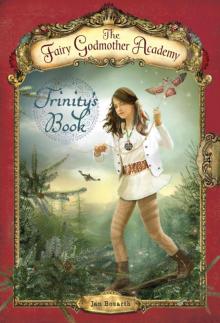

Sumi's Book Trinity's Book

Trinity's Book Kerka's Book

Kerka's Book