- Home

- Jan Bozarth

Zally's Book

Zally's Book Read online

Praise for Kerka’s Book

“This sparkling combination of action and magic is bound to enchant.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“Excellent…. The writing is refreshingly well done and weaves together the author’s knowledge of art, folklore, and botany to paint a magical world where readers’ senses are piqued by the likes of stone fairies, cave anemones, and a queen named Patchouli.”

—SLJ

“Great for girls who love fairies and magical worlds.”

—KidzWorld.com

Praise for Birdie’s Book

“Bozarth’s tale is a beguiling mix of magic, adventure and eco-awareness, and her message of girl-power and positive change will resonate with tween readers.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A fun, light read that ought to be a hit with girls who like adventure and magic.”

—Books for Kids (blog)

“Bozarth has taken the best aspects of various young adult genres and mixed them together in a fresh and optimistic way.”

—Kidsreads.com

The Fairy Godmother Academy

Birdie’s Book

Kerka’s Book

Zally’s Book

Dedicated to my friend Meredith Dreiss

and my Cuban family

Contents

Cover

Other Books by this Author

Title Page

Dedication

1. The Bakery

2. The Arrival

3. The Quest

4. The Long Road

5. The Marsh

6. The Jungle

7. The Innocent

8. The Thief

9. The Web

10. The Kib Valley

11. The Healing

12. The Magic

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

1

The Bakery

The last Saturday in October, a week after my thirteenth birthday, was awesome. Autumn in New York City can have practically any kind of weather, from warm Indian summer, to clear and crisp, to rainy and miserable. That day the trees along the streets of Manhattan wore their most beautiful fall leaves, and there was a hint of chill in the air. It was a perfect day to sleep in, have a lazy brunch, and then go for a walk in the afternoon. I love to wander around with friends, poking through the things that street vendors have for sale, eating hot pretzels, riding the carousel in Central Park, or watching tourists in the horse-drawn carriages.

Unfortunately, there is no such thing as a lazy Saturday in the Guevara family. That’s because my parents own a bakery on the Upper West Side, and everybody in our family works there—from my mother’s mother down to José Junior (J.J. for short). We all wake up at four in the morning to get the bakery ready to open at six-thirty for the grabbing-breakfast-on-the-way-to-the-office crowd. Sundays are the only exception. The bakery is always closed on Sundays to get ready for the following week.

I hate mornings. I mean, how many thirteen-year-olds even have a job, much less one that starts at the break of dawn? I don’t usually argue, but once, after staying up too late looking at my world atlas the night before—studying maps of all the countries I’ll probably never get to see—I made the mistake of telling my parents I was too young to work at Alma de Chocolate, which means “soul of the chocolate.” In fact, on the sign outside our bakery, below the name, are the words “We Feed the Soul.”

Papá had given me a stern look. “It’s the family business, mi’ja. We all have to do our part.” (Mi’ja is short for mi hija, which is “my daughter” in Spanish, and that’s what my parents usually call me. My brothers and friends just call me Zally, though.)

Mamá gave a small shrug and said, “It is not so bad. In many places, children much younger than you go to work.”

Abuelita—my grandmother, who is so short the top of her head only comes to my shoulder.—chuckled and said, “In some countries, you are old enough to be married. At least you do not have children of your own to support.” She chuckled again.

I haven’t complained since. Now I just drag myself out of bed, no matter how sleepy I am, and get going. Once I get my body up and moving, eventually my brain wakes up, too.

That Saturday seemed like most Saturdays at Alma de Chocolate. It’s my job to wait on the customers, so that’s what I did. I actually like talking to the people who come in and finding out where they’ve traveled. I ask about what they did and where they stayed, whether there were any cool ruins, and what kind of animals they saw. I want to know everything!

On the counter, we keep a globe that has Guatemala marked with a teensy Guatemalan flag and a sign that says:

A PORTION OF THE PROFITS FROM

ALMA DE CHOCOLATE

GOES TO SUPPORT THE CHILDREN

OF GUATEMALA.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR PATRONAGE.

Anyway, Saturday mornings are slow, and I was doing homework when a man walked into the shop, wearing a baseball cap, a Windbreaker, and a confused expression—definitely a tourist. He had a map of Manhattan and looked disappointed when he saw me behind the counter.

“Oh, I was hoping someone could help me with directions. Never mind,” he said, starting to walk out.

Don’t you hate it when somebody thinks that you can’t possibly know how to do something just because you’re young? “I can help you,” I said, stopping the man in his tracks.

He didn’t look like he believed me, but he turned and came back to the counter. “I’m supposed to meet somebody at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—”

“Simple,” I said. I whipped out a blank sheet of paper and sketched a map of the route through Central Park from our shop to the Met.

Have I mentioned that I love maps? Maps have been a hobby of mine for as long as I can remember.

The man raised his eyebrows as I labeled the streets and told him what landmarks to watch for. I loved his look of surprise. He bought a loaf of bread, a mini magdalena, a couple of chocolate besitos, and a cup of coffee. Then, thanking me, he left with a smile on his face.

I sat back down, feeling like a true New Yorker.

I was born in New York City, but my parents didn’t grow up here; they grew up in a tiny village in Guatemala. After they moved to America, they had to work so hard for every penny that now they never take anything they have for granted. Clothes get passed down or given to a homeless shelter. In the bakery we also find a use for everything. Cans, bottles, paper, and plastic go into recyclers. Day-old breads or pastries get donated to a soup kitchen. On top of that, twice a year my mother travels down to Guatemala with a group of volunteers to build schools. Mamá had been gone for over a week on one of these trips and was due back home on Sunday. When I am fourteen, I’ll get to go—my first international trip!

My favorite form of “recycling” in our family is that whenever somebody in our neighborhood finds a stray pet that has no tags, they bring it to us at the shop. Then one of us carries the animal home and cleans it up. We also take in animals whose owners can’t care for them any longer for one reason or another.

While there were no customers for a few minutes, Abuelita watched the shop and I took the trash out. When I opened the door to go back in, I heard a pitiful meow in the alley. Looking around, I saw a plump gray cat with white paws come out from behind the trash cans. It ran right to me and started rubbing against my ankles, purring as if I were its only friend in the world. I picked it up and noticed immediately that the cat was not plump from being well fed. She was pregnant.

“¡Pobrecita! I bet you could use a soft bed and some good food,” I said. I carried the mommy-to-be into the bakery. With a smile, Abuelita made a shooing motion.

I took our newest stray home, fed he

r, settled her with Papá and J.J., and was back at Alma de Chocolate in twenty minutes. After washing my hands carefully, I started on a new flyer to post in the window.

The bakery closes at five on Saturdays, and my older brothers, Ed (short for Eduardo) and Antonio (“don’t call me Tony”), were there to close down. Abuelita wanted to take the leftovers to a family shelter. My best friends, Malia and Cody, were out of town for the weekend, so I went with her. As an extra treat for the kids, I brought along three kittens.

When we arrived at the shelter, the director, Mr. Duchet, and two of the older kids helped us carry everything inside. It’s funny, but the way those kids lit up, you’d have thought it was Christmas. Not just because of the food, either. They loved the champurradas, conchas, and chocolate empanadas, of course, but they were excited to see Abuelita.

Mr. Duchet, a tall man with wiry black hair, came to stand beside me. “An intriguing woman, your grandmother. It’s magical how she fills a room with warmth.”

I smiled. “It’s like this everywhere she goes. That’s one reason I love to come with her.”

“What’s in there?” The director pointed to my Little Red Riding Hood basket. I lifted the lid and showed him the three sleepy kittens inside.

“It’s all right, isn’t it?” I asked.

He smiled. “I think you’ve got a bit of your grandmother’s gift in you.”

I walked over to Abuelita and handed sleepy kittens to three of the kids to gasps of excitement. After being passed around and petted, the kittens began to explore, climbing onto kids’ shoulders, nosing around, and scampering across the floor. The calico kitten pounced on a shoestring and started pulling it. It was no surprise to me that when our visit was over, Mr. Duchet whispered to Abuelita and me, “Is there any chance we can adopt these furry angels?”

Abuelita grinned.

I nodded at the director. “I think my mother will approve.”

That evening, Ed and Antonio went out with friends after dinner, and Papá worked on the quarterly taxes for the bakery. J.J., who is eight, was bored, so I offered to play a game of Go Fish with him. I pulled my long hair into a ponytail and changed into a soft pink-and-white striped tee and black leggings. Then I got the playing cards and coaxed the pregnant cat out into the living room to lie beside the coffee table while we played.

Abuelita sat next to us in a rocking chair, reading, as usual. She didn’t even look up from her book when J.J. and I pretended to fight about whether he had stolen all the queens from my hand. I shook my finger at him, he poked me, I poked him back, and the argument turned into a tickle fight.

Once J.J. was in bed, I sent e-mails to friends from the family computer in the living room. Then I went to my room to read. Because our family is large—at least larger than most of my friends’ families—my room is tiny. But it’s mine, all mine. I don’t have to share with anyone.

One whole wall is bookshelves from floor to ceiling. We had to get creative to fit furniture into such a small room, so I have a six-foot-high loft bed. In the open area beneath it is my desk. The pedestals that hold my bed up are also bookshelves, one of which is crammed full of atlases and books about cartography, exploration, mapmaking in ancient times, and geography. By the ladder at the end of the bed, a big floor pillow snuggles into the corner of the room, with a light above it.

I was curled up on the pillow, reading Alanna by Tamora Pierce, when Abuelita came in carrying two cups of cocoa. I put my book down and moved the desk chair over beside the pillow, and then we both took a mug of the steaming liquid and drank. Abuelita says she based her special recipe for hot cocoa—which she calls chocolatl—on an ancient Mayan recipe.

I took a long sip of the spicy cocoa. For some reason, chocolatl reminded me of the stories about a fairyland called Aventurine that Abuelita and Mamá have told me since I was a young girl. They only told these fairy tales to me, not to my brothers, and sharing stories and chocolatl among the three women of the family had always been a special time.

“Do you know that there is magic in the cacao?” Abuelita asked.

I smiled. After all, I’m a little old for fairy stories now. But I just said, “Mmm, it’s delicious.”

“Delicious and magic,” Abuelita insisted. Even though our whole family speaks Spanish, she likes to practice her English with us grandchildren (and we have to practice Spanish with her). “Our ancestors, the Maya, and their ancestors before them have known the secrets of the cacao for thousands of years.”

“Thousands?” I asked, not quite believing her.

She gave an emphatic nod. “Yes. The people who dig up the old things, the—¿Cuáles son sus nombres? What are they named?”

“Archaeologists?” I suggested.

Abuelita nodded again. “Yes. Archaeologists. They find the old, very old, pots with just some little of cacao at the bottom. Also, the cacao beans were muy valioso, very valuable. The Maya gave them for presents or used them as money. Sometimes it was a gift when the child reaches a certain age.”

It sounded like a strange present to me. I had plenty of friends who had had parties to celebrate growing up, like my friend from school Rachael. She’d had a bat mitzvah. I celebrated my First Communion when I was nine, and Alicia, who lives in the apartment upstairs, had a quinceañera when she turned fifteen. But I’d never heard of anybody getting cacao beans as a gift for one of those occasions.

“How old did you have to be for that?” I asked curiously.

Abuelita studied me for a moment with her shining dark eyes. “Que son mayores de edad. You are old enough.”

“Um, thank you?” I replied, a bit confused. As far as I knew, there were no ancient coming-of-age traditions in our family. Maybe she hadn’t understood my question.

Just then, Abuelita pulled a small object from a pocket in her apron and held it up. It looked like some kind of fruit, about the size of a papaya, with a yellowish brown rind. “This is the cacao pod,” she said. “A small one, yes, but muy viejo, very old. It is especial—in our family many generations. It is for you now, nieta.”

I accepted the pod carefully. “Thanks,” I said.

“Your mother and I are already the hadas madrinas—fairy godmothers. You will need this to become one as well,” Abuelita said.

That stopped me in the middle of a gulp of chocolatl. I sputtered and coughed. “Fairy godmothers? Real ones, like in Cinderella, you mean?”

Abuelita explained that the magical abilities of fairy godmothers are passed down from mother to daughter, from one generation to the next. Then she said that fairy godmothers aren’t just for people, but for all parts of the earth. I didn’t really believe it. I mean, it felt weird talking about magic as if it were real! But as my grandmother spoke, I realized that she and Mamá talked about magic all the time. Finally Abuelita said that I, Zally Guevara, am the heir to the Inocentes Lineage. Each girl in a line of fairy godmothers is born with gifts, and through magic, those gifts can be developed into skills that the fairy godmother can use to help the world for the rest of her life.

“You’re trying to tell me that I can do magic?” I asked.

“To some people it is magic,” Abuelita said cautiously. “The women of the Inocentes Lineage have a special gift for helping innocents—children and animals. You will learn more in Aventurine.”

I just stared at her. My lips made the word “Oh,” but I didn’t say anything as things clicked into place—the way people’s faces lit up when they saw Abuelita, the way Mamá helped build schools, the way my family attracted animals. And I’d always liked kids and animals, and they seem so comfortable with me. So that was a gift, huh? Okay, maybe I didn’t completely believe in Aventurine, but I could accept that the women in our family had an amazing talent.

“Where is Aventurine? Can you show me on a map?”

“You will find it, but not with a map. Aventurine has never been mapped,” Abuelita said.

“It should be,” I said. “With a map, you can never get los

t.”

Abuelita clucked. “That is like saying if you have a good recipe, you are a good cook. In truth, to use a map properly, you must know where you are. But there is knowledge that comes from the heart. Even for you”—she touched her hand to her chest—“el corazon es su mapa. And you must keep the cacao pod,” she said. “It is important.”

I had more questions, but I wasn’t sure I was ready to ask them. Wouldn’t that be admitting that it was all real—fairy godmothers and magical lands? It wasn’t that I didn’t want it to be true, but I needed time to think. I stared down at the cacao pod in my hand. “Okay. I’ll keep it safe and always keep it near me. Look,” I said, getting up and slipping the pod into my favorite bag, a Maya-patterned one that hung from my ladder. Abuelita seemed to like that.

“Good.” She walked to the door of my room and then turned. “Drink the rest of your chocolatl. It will help you rest well. Tomorrow morning you can sleep a little late, I think.”

2

The Arrival

Something woke me up, but it wasn’t an alarm clock; it was a tickling on my nose. I scratched my nose without opening my eyes and tried to go back to sleep. The light was bright, and I wondered if I had overslept. Then I remembered Abuelita had said that I could stay in bed a bit longer.

There it was again, the ticklish feeling, as if a spiderweb were brushing against my face. The thought of a spiderweb gave me a chill, because I’m really afraid of spiders. I opened one eye, only to discover that the tickling came from a set of long whiskers.

A black and white rabbit sat by my head.

Curiouser and curiouser, I thought. How had a rabbit gotten up onto my loft bed? I opened my other eye and looked around. I wasn’t in my room, or our apartment, or our building, or—as far as I could tell—even New York City.

Zally's Book

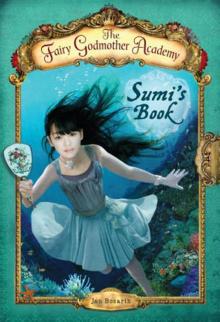

Zally's Book Sumi's Book

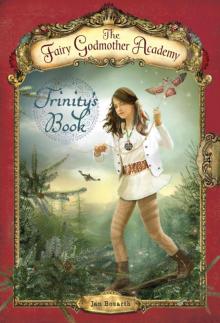

Sumi's Book Trinity's Book

Trinity's Book Kerka's Book

Kerka's Book