- Home

- Jan Bozarth

Zally's Book Page 2

Zally's Book Read online

Page 2

I sat up and rubbed my eyes. I was at the edge of a broad grassy meadow. My woven bag from Guatemala was beside me. The grass was a bright spring green, sprinkled with wildflowers. Butterflies fluttered over my head, playing tag with each other. Could I be dreaming?

I picked up my bag and looked inside. The cacao pod was still there. Otherwise, the bag was empty. Putting the strap over one shoulder, I got to my feet and brushed bits of grass from my clothes. I noticed I was barefoot and dressed in the same clothes as when I’d read in my room last night. Had I been too tired to put my pajamas on after drinking chocolatl with Abuelita? I couldn’t remember.

A few shimmering hummingbirds flitted around the wildflowers and darted off. I turned to look behind me. There, a gurgling stream ran through the center of the meadow. Dozens of willow trees draped their branches along the stream. This place, whatever it was, seemed more natural, more real to me than any place I had ever been—and at the same time, less real.

And suddenly there she was. From between a couple of willows, I saw a lady coming toward me. No, not a lady, a fairy—a real fairy! And not the tiny little you-can-hit-it-with-a-flyswatter type of fairy, but a fairy taller than me with iridescent blue wings that opened and closed like a butterfly’s. Flowers twined through her dewdrop crown. Her hair flowed to her knees, and she wore a beautiful gown of the palest lilac. The scent of lilacs hung about her as well. A cascade of tiny silver bells on her earrings made a tinkling sound when she moved her head. She stopped a few feet away from me and said, “Welcome, Zally.”

That was when I knew it: I was dreaming. Still, I wanted to be polite. So I gave a small curtsy and said, “Thank you … Your Majesty?”

She smiled. “You may call me Queen Patchouli. Come with me.” She waved a dainty hand toward the trees. “We should get started right away. Do you have any questions?”

Questions? I had lots of questions! I blurted, “Why—I’m just asleep, right?”

She tilted her head and looked at me. “You may be sleeping in your own world, but you are awake here. And this is no ordinary dream. This is Aventurine. You could spend hours or weeks here while you’re asleep in your own world. But you’ll wake up in your own bed, and only one night will have passed.”

My mouth fell open. “Did you say Aventurine? It—it’s real?”

She laughed, and I followed her down to the stream. We began to walk along it, the grass tickling my bare feet.

“Are you the queen of all Aventurine?” I asked.

“I am the queen of the Willowood tribe of fairies,” Queen Patchouli answered. “There are many more fairy queens throughout the land, each with her own queendom.”

“How many fairy godmothers are there?” I asked.

“How many people are in a family?” she asked me in return.

“How much of my family do you mean? Just my parents and brothers and me? Six. With Abuelita, seven.”

The fairy queen said, “That is just your family. But how many people are in any family?”

“That depends,” I answered. “Some families are very small. Or should I include cousins and aunts and uncles and grandparents—great-grandparents, even? There are lots of ways to count family members, so there’s no easy answer.”

She nodded. “That’s how many fairy godmothers there are.”

I tried a different question. “Do I know any other fairy godmothers?”

“You know your mother and grandmother, don’t you? You will learn to recognize others.”

“How long does it take to become a fairy godmother?” I asked, trying to get a real answer from her.

“How long does it take someone to become a brilliant musician?” Queen Patchouli countered.

“Everyone’s different.” I frowned. “Some people don’t want to become musicians. Some never get really good at it. Others are great right away. Then there are people who have to work hard for years until they get to the same point.”

“Exactly,” said Queen Patchouli.

Eventually we passed through a grove of trees, then out into a glade. There, more fairies walked or flitted about doing their work—whatever it is that fairies do. At the center of the glade stood a small desk and chair. On the desk was a stunning leather-bound book the size of a dictionary. I wondered if it might be an atlas, and hurried forward to look.

“This is The Book of Dreams, Zally,” Queen Patchouli told me. “Before we discuss anything more, I need you to write your dream in it.”

“But I usually don’t even remember my dreams,” I said.

The fairy queen smiled. “Those are not the sorts of dreams that are entered in The Book of Dreams. The book is for your hopes and desires. You could just write a hope for today, but far-ranging dreams are more satisfying for the book.”

“Okay,” I said, wondering if I really had a choice.

The queen motioned for me to sit at the desk.

I put my bag on the table by the book and sat down. “So Mamá and Abuelita wrote in here?”

“Yes,” the queen said, “as the other women of the Inocentes line did before them. But not every girl who could become a fairy godmother does become one. Some girls choose a different path. And some …”

“They don’t make it?” I asked.

She nodded.

I swallowed hard.

“So, now you will write in The Book of Dreams.” Queen Patchouli waved her hand. A snow-white peacock appeared, strutting toward us. The bird fanned out its sparkling tail feathers proudly, nearly blinding me as they caught the sunlight.

“We need one of your feathers, my beautiful friend,” Queen Patchouli said.

Turning its back, the peacock shook itself, sending out a shower of light, and released a glittering white feather from its tail. The plume drifted gently to the ground. Murmuring her thanks, the fairy queen picked up the quill and placed it on top of The Book of Dreams. Then she lifted the lid off a shell bowl that sat near the book. Inside was a silver liquid.

“Your pen,” she said, touching the feather. “Your ink.” She pointed to the shell bowl. “Your paper,” she said as the pages turned on their own and opened to a blank one.

“Can I read what Mamá and Abuelita wrote?” I asked.

The fairy queen answered, “Perhaps, but you must write your dream first.”

I took a deep breath and picked up the feather. I dipped the end into the silver ink and wrote the first thing that rose to my mind.

October 25, 2008

I want to travel to different lands, meet new people, see animals I’ve only heard of. Plus I want to make a map of my travels. Most of all, I want to make a map of Aventurine, because there isn’t one. I want to help other girls who need to find their way, by making a map to help them on their travels, too.

—Zally Guevara

I closed my eyes and pictured what I had already seen in Aventurine. Then, dipping the peacock quill back into the ink, I drew a map at the bottom of the page of the meadow, the willow trees, the stream, the forest, and the fairy glade. The ink dried instantly. A moment later, more details surfaced in the margins, and my silver lines were filled with brilliant colors until the page looked like an illuminated book from the Middle Ages.

A breeze blew in and ruffled the pages of the book again. It opened to a dream written in Abuelita’s handwriting….

The pages fluttered, and The Book of Dreams closed with a thump. I was still in a bit of a daze when a new question occurred to me. “Abuelita said that we’re of the Inocentes Lineage of fairy godmothers—women who help innocents. That’s not what I wrote about in The Book of Dreams, though. What does making maps have to do with helping innocents?”

Queen Patchouli motioned for me to stand; then she led me down a new path. It looked like it was made of crystal shards, but it was soft against my bare feet.

The fairy queen considered my question before answering. “You will be helping fairy-godmothers-in-training who come after you to find their way when they go on their quests. It is a special gift t

hat you have. No one has mapped Aventurine before. But mapping is not the only ability you will develop on your quest. Simply by going, you will learn many skills you need for helping innocents.”

“Quest?” I asked. “What do you mean?”

“You will soon find out,” said the queen.

“And what exactly is an innocent?” I asked. “How can I tell if someone is innocent?”

Queen Patchouli tilted her head. The tiny bells on her earrings tinkled. “The fairy godmothers of the Inocentes Lineage are not asked to judge who is good and who is evil so much as they are expected to help those who are in need—especially those who cannot help themselves. You will learn to recognize innocents, and you will be drawn to those who most need your help.”

¡Ay, mira! That seemed like a lot to expect. I mean, I was just barely thirteen, and I thought working in our bakery was too much responsibility sometimes.

“We are here. You must get ready now,” the fairy queen said, glancing down at my bare feet. She made a swirling motion with one hand.

A circle of grass sprang up, like water spraying from a fountain. But instead of falling back down as water would, the ring of grass—almost ten feet high—stayed in place, swaying in the faint breeze. From the edge of the grass circle all the way to my feet, a pathway of springy soft moss, dotted with white flowers, grew in just a few seconds.

“Take your bag,” Queen Patchouli said. “Everything that you need will be in there.”

Picking up my bag from the ground, I felt for the cacao pod family talisman inside. It was still there. Then I walked down the path and used both hands to separate the stalks of grass at the edge of the circle so I could look inside. The circle was hollow. It formed a tiny roofless room, like a changing room in a store—only alive. I stepped in, admiring the wildflowers that carpeted the ground. There was nothing else in the room.

I slipped the bag off my shoulder, and something sprang out of it. I dropped the bag and backed away. The something looked like a leafless tree branch. It hovered at the same height as the grass of the circle. It started to thicken and become more rectangular; then it elongated in several directions. Little flaps of wood unfolded with a clatter, until a wooden wardrobe stood before me.

Yes, I said wardrobe. The dark wood at the base was carved with flowers. From the top of the wardrobe, a sun with a carved face smiled down at me. I was still a bit spooked by the jack-in-the-box trick, so I was very careful when I stepped toward it. Who knew? A whole department store might pop out! Then again, the wardrobe might be filled with fur coats and mothballs, and the back might lead to another new world….

As it turned out, neither thing happened. I looked around on the ground for my woven bag, hoping my family talisman hadn’t been squashed. I didn’t see the bag, so I stood to one side and pulled open one of the wardrobe doors. An ordinary mirror was attached to the inside, reflecting my tense body and cautious expression. Relaxing, I opened the second door. Another mirror. In the wardrobe was a long rod with clothes of every kind and color hanging on it. Below that, there were drawers filled with gloves, belts, hats, and dozens of other accessories. A flat area on top of the drawers displayed all sorts of shoes, boots, sandals, and slippers. And everything looked my size!

From outside, the fairy queen’s voice said, “Take what you need now. This will be your only chance to prepare for your journey.”

How was I supposed to know what I needed? I finally decided that I should be practical. I chose a pair of brown leggings, a light-as-air pink cotton shirt that had billowy sleeves, and a cropped brown vest that reminded me of Guatemala, with flowers embroidered all over it. Then I pulled on a pair of purple boots that went up to my knees. They were made out of a material I’d never felt before—something between silk and leather.

When I was satisfied, I picked up an armful of the clothes I had tried on, to put them back. Suddenly I heard a whooshing sound; then a force like the wind pulled the clothes right out of my hands, except for one long silky scarf, which wrapped itself around one of my wrists. Moments later, all of the clothing—except for what I was wearing and the scarf—had returned to its proper place. Next, even faster than the wardrobe had assembled itself, it shrank back into my bag and disappeared, like smoke being sucked into a vacuum cleaner.

I lifted my bag, half expecting it to weigh a ton, but it felt completely normal. I looked inside. The cacao pod was there. I tucked the scarf, which was the light purple of early dawn, into the bag and slung the bag over my shoulder.

Instantly, the circle of grass around me sank into the ground until it was the same height as all the other grass in the area. I could see Queen Patchouli waiting for me.

“What do you think?” I asked, gesturing to my outfit.

“Perfect. Those are special waterproof boots,” the queen said. “I think that you are ready for—”

Just then, a horse and rider galloped up the path and came to a stop right in front of us in a spray of sparkling gravel. The horse, its coat dark with sweat, was a golden palomino with four white stockings and a flaxen mane and tail. The horse shook its head—the mane had golden strands in it, which reflected the sunlight dazzlingly.

Slumped over the horse’s bare back was a girl with wild coral-colored hair. Dirt caked her bare legs and was spattered on her arms. Miniature shells dangled from her earlobes and hung from a chain around her neck. She looked about my age and height. Then I noticed her peach-tinted wings, shimmery and sheer like the wings of the other fairies—but one of her wings was broken.

Turning her head toward us, the fairy girl said, “We need your help.”

3

The Quest

Queen Patchouli lifted a delicate glass bell, which she rang three times. The sound was not loud and definitely not unpleasant, but the effect was astonishing.

In a flash, fairies appeared from all sides. Some ran, and others fluttered in to land beside us on the crystal path. They each brought something: goblets, strips of cloth, buckets of water, bowls of raw vegetables, long sticks of what seemed to be the slender ends of willow branches, and mysterious bits of violet-colored fluff.

The fairy girl was beginning to slip off the horse’s back. Afraid that she might break her other wing, I quickly reached out and caught her. Queen Patchouli helped me lower her gently onto her side on the grass. The girl’s dress, woven in a tiger pattern, was torn and muddy.

The horse’s sides heaved. An amber-winged fairy set a bucket of water before the horse and let him drink a few sips while an identical fairy covered the horse with a light blanket. The twin fairies then coaxed the palomino to walk in a slow circle to cool down.

The queen swept her arms out wide. The rest of the fairies set to work at an almost feverish pace. A fairy with fuchsia wings offered the fairy girl a goblet filled with clear liquid.

“It should help the pain,” Queen Patchouli said.

As the fairy girl accepted the cup, more fairies sat down beside her. They dipped the strips of cloth into the buckets of warm water and wiped dirt from her face and arms. Another fairy untangled her long coral hair with a comb carved from wood.

When the horse was cooled down, the twin fairies removed his blanket. Three fairies with iridescent wings flew in over the horse. They emptied bucket after bucket of cool water over his back, head, and flanks. One of the amber-winged fairies fed him fresh carrots.

During all of the activity, Queen Patchouli very seldom spoke, except to say, “There,” or, “Over here, please,” or, “Yes, thank you.”

Soon, the tiny bits of violet fluff sprang into action. Although they looked vaguely like purple caterpillars, they moved fast. Dozens of the fluffs hopped onto the horse’s coat and jiggled around like miniature scrub brushes, removing dirt from the animal’s back. More of the fluffs cleaned the fairy girl, who stayed silent.

When the baths were done, one fairy talked softly to the horse, who kept looking over at the injured fairy with a worried expression. Finally the horse folded

his legs beneath him and lay down. He seemed to fall into a deep sleep. Then all the fairies disappeared into the woods. Queen Patchouli picked up several long pieces of whip-thin willow stick and handed them to me. She knelt next to me, beside the injured fairy, who hissed with pain when we had to straighten her broken wing.

“I’m sorry. We’ll try not to hurt you,” I said.

“Follow this pattern,” Queen Patchouli instructed me, tracing her finger along a line in the wing that looked like the vein of a leaf. Even though I wasn’t quite sure what I was doing, I watched the fairy queen and tried to do on the front of the wing whatever she was doing on the back, so that my work mirrored hers.

“This is quite a serious break,” Queen Patchouli murmured. Her brows drew together with concern. “The Willowood Fairies do not have healing magic for something this serious. All I can do is make a special support for the wing so it can get better on its own.” She handed me a soft white strip that looked like a satin ribbon.

“How long will that take?” I asked.

“A year or more,” Queen Patchouli answered as she placed a silky strip over the willow splint on her side of the girl’s wing and smoothed it down. It stuck in place like the tape they use at a doctor’s office.

I did exactly what she had done, and the piece of ribbon on my side of the wing stuck and held the willow in place as well. We both picked up another piece of willow and began to secure the next part of the wing. “A year? Is that normal?” I asked in surprise. “Bones usually heal in a few months in our world. She’ll be able to fly before then, won’t she?”

The fairy girl’s eyes had drifted closed while we worked.

“I’m afraid not,” Queen Patchouli said. “If she puts any weight on her wing before it is fully healed, she risks a worse break and may never be able to fly again. Only Queen Carmina in the Kib Valley has the healing power that can fully mend this wing.”

At this, the golden horse raised his head, shook his mane, and whinnied loudly. The fairy girl’s eyes opened wide.

Zally's Book

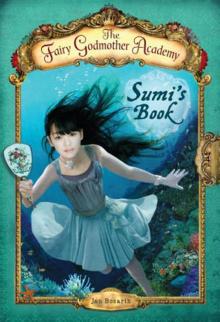

Zally's Book Sumi's Book

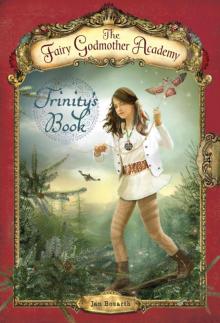

Sumi's Book Trinity's Book

Trinity's Book Kerka's Book

Kerka's Book