- Home

- Jan Bozarth

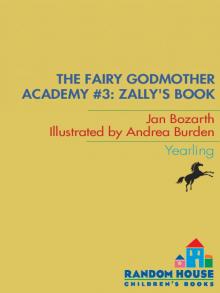

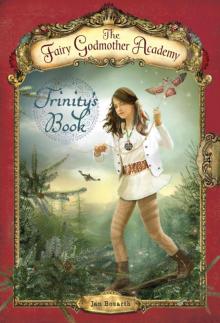

Trinity's Book Page 7

Trinity's Book Read online

Page 7

“Walk off!” A wrinkly little toad-man jumped out of the brush. His legs were so short he looked like a ball resting on two frog feet. “Walk off!”

Several other round men stepped out of the brambles and surrounded me.

“Walk off! Walk off!” they chanted.

“What’s a walk off?” I had a good idea, but I had to know for sure.

“The quickest way to leave the tree is to walk off it.” Hoon’s upper lip curled into a sneer.

I gasped. “But I’ll die!”

A toad-man looked up at me and grinned. “Walk off, fall down, die.”

“Yes,” Hoon agreed, “unless you’re a true creature of the Cloud Pine Forest, like the Curipoo and black-spot lizards and a thousand other tree-dwelling beings and beasties. Then you’ll survive.”

The lizard and the Curipoo were creatures of the Cloud Pine Forest, but they couldn’t fly. So they’d flunk Hoon’s tree test, too. But at the moment, I didn’t think logic was going to convince Hoon that his test didn’t make sense. I quickly realized that I didn’t have many options. Those I had weren’t very good, but I had to try.

“I’d like to eat a last meal first,” I told Hoon.

My plan was simple: Perhaps my captors would get bored waiting for me to finish the never-gone sweet potato and fall asleep. Then I could escape up the tree.

Hoon, however, was too anxious to kill me to grant a last request. “No.”

With plan A down the gurgler, I moved on to plan B: If I anchored the unbreakable string, it might act like a bungee when I fell. Then I could grab a lower branch and find another way up the tree.

I shifted the harness and reached for the spool.

The Hydra slapped my hand away and tried to pull the harness off.

“No, please! Let me keep it. A harness pack is the most prized possession of my people,” I lied. “If I’m going to die, I want to die with my pack on, like a real … cowboy.”

I knew American cowboys liked to die wearing some kind of gear—boots or a hat? I wasn’t sure what, but the Keeper of the Cloud Pine Forest didn’t know, either.

“What do you carry in there?” Hoon asked suspiciously.

“Food, a water pod, and string,” I answered honestly. I touched the kite. “Uh … a Curipoo gave me this.”

“Top bark and sticks?” Hoon scowled, then snorted. “Keep it all! You’ll be heavier and will fall faster.”

Again, I decided not to reason with him. Although I was dying to say that weight had nothing to do with how fast things fall, only wind resistance and an object’s aerodynamics could slow it.

He brushed past me and stopped a few feet farther on. He waited with his back turned, expecting everyone to follow.

A toad-man poked me with a giant thorn. “Walk now!”

The others raised thorns to jab me if I didn’t obey.

I walked.

Hoon led the way down the branch, using his staff as a walking stick.

A well-worn path cut through the jungle of black vines and twisted tree branches. As the old man’s minions herded me along, I wondered how many other unsuspecting travelers had been shoved off the branch. The toads were so excited about my imminent plunge to certain death that I was pretty sure it didn’t happen often. Still, the thought made me angry, and my mind went into overdrive. I was still alive, and as my American friends liked to say, “Where there’s a will, there’s a way.”

I had the will and another idea. Although plan C was based on science, not magic, it still required a leap of faith on my part. If I was right, I would live.

If not—

“Halt!” Hoon stopped and spun around to face me.

Beyond him, I could see a secondary branch that grew straight out from the main limb. It was about three feet wide, six feet long, and smooth as a board on top.

Like a plank on a pirate ship, I thought, but with one significant difference. If I walked the plank on a ship, I’d land in water. The ground below this plank was hard and a long, long way down.

“You wait!” one of the round men snapped as all the little guys closed in.

Hoon raised his staff and spoke in a booming voice. “We come to cast out one who is not of the Tree!” He fixed me with a cold stare. “Or to prove she belongs.”

“No tree she!” a toad-man yelled.

“No tree she!” the others chanted. “No tree she!”

“I have permission! Queen Patchouli sent me to climb the tree.” The partial truth was a gamble, but it was worth a shot.

“Did she now,” the old man sneered. “Why?”

I lied again, hoping he respected Queen Patchouli’s authority like the Curipoo. “I’m, uh … on a goodwill mission—like an ambassador.”

“Intruders are no good!” Hoon exclaimed. “The punishment for trespassing is as it always has been and will be forever and ever. The prisoner will walk off—now!”

The round man to my left waved his thorn and shouted, “You walk off!”

Two more waddling toads stepped out of the bushes. One held a round drum under his chubby arm and beat it with a stick. The second guy blew an ear-piercing whistle every few beats.

“Walk!” Hoon ordered. He pounded the ground with his staff, keeping time with the drum.

I dug in my heels, but the little men pushed and prodded me with thorns until I was on the plank branch.

“All right!” I shouted, and held up my hands.

The despicable toad-guys stopped—just short of stepping onto the branch with me.

That’s one thing in my favor, I thought. They were afraid to walk out on the branch. I wasn’t sure plan C would work, but it had a better chance if I was on the plank alone.

“Stalling won’t save you,” Hoon said.

“I’m not asking to be saved,” I said. “I just want to die a warrior’s death—bravely with a few final words to my ancestors.” I didn’t flinch as I met his black gaze. “Without being pushed.”

“I will not deny you that,” Hoon said, “just hurry up about it.”

I pulled the Ananya talisman out from under my tunic and opened the top. I needed information, but I didn’t want the horrible old man to suspect my intentions. I composed a chant off the top of my head.

“This Ananya daughter must ride the sky!” I moved farther out onto the branch and spoke as though I were imploring the spirits of my family. “Please take me swiftly and lift me up, whichever way the wind blows!”

The inside of the pendant mechanism clouded and then coalesced into a diagram. The image was similar in style to the hologram over Queen Patchouli’s stone table, and the meaning was clear: The wind was moderately strong and blowing away from the tree.

“Enough!” Hoon glared at me. “Walk off now!”

“As you wish.” I grabbed my kite, ran to the end of the plank, and jumped off the branch.

I dropped like a rock.

The toads laughed and chanted. “Walk off! Fall down! Walk off! Fall down!”

For a terrifying moment, I thought I had horribly miscalculated everything: wind speed, my kite’s lift, and a not-quite-but-almost belief that I could fly.

“You dead now!” a little man yelled.

The others chimed in. “Dead now! Dead now!”

Not dead yet, I thought. As the bottom fell out of my stomach, I reached for the sky and angled the kite to catch a current of air.

The silky bark fluttered and then stretched taut in a sudden updraft. I laughed as the kite rose higher and flew past the astonished little men on Hoon’s branch.

“Fly away!” The toads bounced and clapped, enjoying my flight to safety as much as they had anticipated my demise. “Fly away!”

“No fair!” Hoon stamped his feet and shook his staff. “Fairy godmother brats can’t fly!”

This one can, I thought, when the wind and the kite are strong.

So far I had climbed straight up from branch to branch in a vertical line. However, the giant tree was round with limbs on all sides.

They were just spaced too far apart on the massive lower trunk to see. The major limbs were closer together now, and the wind carried me out and away from the Keeper’s branch to the next one up and over.

I quickly learned a basic method of steering and aimed for the middle of the limb. Just before I reached it, I flipped the top end of the kite toward me and pushed in on the flap end. That slowed me enough to touch down. I stumbled forward, grabbed a smaller branch, and jerked myself to a stop.

The plants on the new branch were similar to the thorn thickets and blood-black leaves on Hoon’s branch, but not as gruesome. The vines were green and supple and the leaves were red with green veins. I didn’t see any menacing Hydra plants or nasty little toad-guys, but I was wary and watchful as I made my way across the limb.

The flight from Hoon’s branch had been quick and easy compared to the climb. If I could do it again, I’d save time and energy. I stood on the edge of the branch with a clear view of the next branch higher up and over on the trunk. Leaving nothing to chance, I opened my compass and checked conditions again. They were exactly the same. I raised the kite and flung myself into the sky with the boldness of an eagle. The kite instantly caught the wind.

I continued flying from branch to branch on a route that spiraled up and around the tree. The distance was greater, but I traveled much faster. I also got lazy and overconfident as the afternoon wore on and the mechanics became routine. I didn’t realize that the major limbs were growing closer and closer together until a small branch caught the side tip of my kite and pulled the silky bark out of the notch.

I lost my balance, tumbled onto the rough bark, and rolled to a stop.

Alarmed by my loud, undignified entrance, a round, fuzzy yellow creature with fangs scolded me from the side of the tree trunk. Two other vampire tennis balls tried to hoist the fallen kite into a hollowed-out gnarl.

“That’s mine!” I got to my feet and rolled up the unbreakable string as I moved toward the kite.

The yellow creatures hissed and shrieked, but when I got too close, they dropped their prize and fled into their hole.

The damage to the kite was minimal, and I quickly made repairs. Then I attached it to my harness. The branches above were even closer together, and I didn’t want the kite to get tangled and broken. Flying was more efficient and fun, but I still liked climbing trees the old-fashioned way.

The vines and other plants had thinned out, giving the tree’s offshoot branches room to grow. There were plenty of places to hold on, and I had no trouble maintaining a brisk pace. I didn’t know how high I had come, but it had to be at least a mile.

The life-forms on the higher branches were just as awesome and diverse as those on the superhuge limbs below. I climbed through a cloud of blue butterflies that jangled like bells, I shed tears when a fungus-clam spit onion juice in my face, and I gagged when my hand sank into a mushy melon plant. The melon closed around my arm and sucked it in past my elbow. I pulled free, but the mush on my skin hardened like cement and smelled like turpentine mixed with rotten tomatoes.

As though Aventurine decided I deserved a break, I found a natural spa on the next branch.

I stood for a minute, surveying the surroundings and hoping my mind wasn’t playing tricks. Logically, the lush gardens and gurgling hot springs couldn’t possibly exist in the top of a tree.

But this was a fairy world, and anything was possible. Adorable puppy creatures and grumpy toad-men had proven that.

I still didn’t move, wondering if there was a catch.

Giant ferns and multicolored flowers grew around the tiered rock walls that formed several pools.

I moved slowly toward one of the smaller pools. I desperately needed to wash off the melon mush crust on my arm. My presence didn’t seem to bother the furry otterlike creatures that dove playfully in the water. Either they didn’t notice me or they didn’t feel threatened.

I paused at the edge of the pool. The water was so clear I could see the bottom. The pool wasn’t deep, and nothing swam, crawled, or walked on the smooth rock floor.

I put my hand in to test the water temperature and sighed. It was hot but not boiling—like a bath made for soothing sore muscles.

“Is it all right if I take a bath?” I asked no one in particular.

When no response came, I stripped off my harness and clothing and slipped into the water.

The warm spring began to bubble, and I stretched out with a contented sigh. The hardened mush and other debris I had collected in my hair were washed away, and the heat eased the tightness in my muscles. Using a lily pad as a washcloth, I carefully cleaned a few scratches and scrapes. Then I languished in the soothing bath until I caught myself dozing off.

When I finally made myself get out, I realized that I didn’t have a towel, but the moisture on my skin evaporated quickly in a light breeze. I dressed, ate the rest of my Curipoo food, drank some water, and fell asleep under a canopy of ferns just as the light faded from the sky.

It was still dark when I woke up.

Stiff from sleeping on the ground, I sat up slowly. My hat, backpack, kite, and harness were all in a neat pile by my side, right where I had left them. I drank some water and ate as much never-gone sweet potato as I could stomach. I didn’t know how much farther I had to go to reach the Cantigo Uplands, but I was pretty sure I wouldn’t be fed when I got there.

When I saw light through leaves, I strapped on my harness, made my way back to the trunk, and started climbing again.

Half an hour later, I began to feel uneasy. Thirty feet farther up, goose bumps rose on my arms and my heart began to beat faster. It wasn’t based on evidence of any kind. I just had a feeling that something terrible lay ahead. Premonitions defied logic, and I usually rejected such things as ridiculous hysteria. However, with Hoon’s attempt to kill me fresh in my mind, I decided to err on the side of caution.

I slowed my pace and moved forward on high alert.

The higher I climbed, the more intense the feeling of dread became. On edge and wary, I paused when I noticed swirls of black mist above me. Thick and opaque, it covered the entire length of the next branch, obscuring everything.

The danger was definitely there.

But I couldn’t turn back. And yet, I couldn’t charge ahead, either. Climbing as quietly as possible, I entered the mist and paused to get my bearings. The interior of the cloud wasn’t as dark or dense as it appeared from the outside. I could see through the haze. I just couldn’t make out many details.

My ears, however, worked perfectly, and I was drawn to the sound of distressed squawks, chirps, hoots, and screeches.

Determined not to be captured again, I crept from one gnarl in the branch to another. Most of the non-tree vegetation was dead or dying. I wanted to avoid whatever sinister being was in control here, but I couldn’t ignore the sound of cries for help.

The noise was coming from a clearing filled with the stumps of large chopped-off branches. I crouched to avoid being seen and peered through the mist. Birds of all sizes and descriptions were locked in cages that hung from branches or were stacked on the ground. Some of the prisoners were shackled and chained to stumps. Dented water buckets and rusted feed pans were scattered around, none within reach of the captives. Their misery and fear was so great I could feel the weight of it in my heart.

I couldn’t leave the birds here to suffer.

But I couldn’t act until I knew the enemy.

I didn’t have to wait long.

A woman emerged from the mist, pulling a wagon topped with a cage. She walked stooped over with a slow, shuffling gait and used a crooked cane. Her gray hair was tangled, and her black dress was tattered and patched. She was so thin she looked like a skeleton covered in wrinkled, gray skin. I didn’t realize what she was until she turned to hit one of the hanging cages with her cane. Blackened wings hung limply on her hunched back.

The woman was a fairy!

“Stop whining, you stupid bird!” The dark fairy’s voic

e cracked, and she smacked the cage again. “You should thank me for feeding you.”

The bird in the hanging cage appeared weak from hunger, but it squawked in brave defiance. “I only pity you, Kasandria. You’ll never fly again.”

“You won’t, either!” Kasandria hit the cage repeatedly, sending a flurry of red and black feathers flying everywhere. Then, her anger and energy spent, she pulled the wagon into the center of the clearing and stopped.

For a moment, I thought the bird in the cage had keeled over and died. I was relieved when it climbed back onto its perch.

“Look at me, lazy birds!” Kasandria screamed. “I have a new pet!”

A few of the birds looked up. Most cowered in their cages or hid behind stumps. The mound of blue and gray feathers in the wagon cage didn’t move when Kasandria opened the door. She clamped a shackle and chain around the bird’s leg and pulled it out.

“Don’t be shy.” The evil fairy cackled and thumped the bird on the back when it tried to hide its head.

I couldn’t believe my eyes. The new bird looked like a moa, though its neck and legs were too short and it only stood three feet tall. Wingless, the huge New Zealand moa had been hunted to extinction by the Maori hundreds of years ago. Judging by its size, this one was only half-grown.

“Now fly, Moa!” Kasandria demanded.

“I can’t,” Moa said.

“Of course you can!” The fairy glowered at the poor creature. “You’re a bird.”

“I don’t have wings,” the bird explained.

Kasandria hesitated, as though Moa’s statement was too incredible to believe. When she stepped closer and ran her hands over the bird’s body, she discovered that he really didn’t have wings.

“I want birds that can fly!” Enraged, Kasandria swung her cane at Moa’s head. He ducked, and she missed. “So I can make sure that they don’t!”

Moa tried to run.

Kasandria grabbed the end of his chain, looped it through another bird’s cage, and secured it with the lock from the wagon.

Then she went berserk.

“Queen Patchouli did this!” Kasandria chased a round, white chicken and then smashed a lantern. She tore vines and dumped feed pans. “She made a bird with no wings to taunt me! I won’t have it!”

Zally's Book

Zally's Book Sumi's Book

Sumi's Book Trinity's Book

Trinity's Book Kerka's Book

Kerka's Book